Summaries

Others:

FAQ/Backgrounder on the Issue and Constitutional Law

Find everything you need to know about the upcoming carbon pricing reference case here. Feel free to leave us questions below or contact us here.

Case name – Constitutional Questions Act Reference re: Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act

File number – CACV3239

February 13-14, 2019, at the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal in Regina, Saskatchewan (map). The proceedings will be streamed live.

This is a reference case regarding the constitutionality of the federal government’s (FEDGOV) legislation called the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act (GGPPA) (see question #4 for more information on the GGPPA). Constitutional cases typically try to answer one main question: does the government in question (in this case, the FEDGOV) have the legal authority to enact a piece of legislation?

This case is going to court because the Government of Saskatchewan (GOVSK) is challenging the GGPPA as being unconstitutional (otherwise known as “ultra vires“, which means “beyond the powers”).

The GOVSK is challenging the GGPPA through a “reference case” or “reference question”. Reference cases are not like the typical lawsuits that involve two litigating parties. Reference questions give governments the ability to ask courts important legal questions. The court’s determinations are not legally binding like a judgment or order in traditional litigation, but governments typically treat them with the same weight and will follow the court’s decisions.1

Other parties who have an interest in the issue can get involved by applying to be an “intervenor”. Intervenors can includes other governments, non-profit organizations, or corporations (see question #7 for the list of parties and intervenors).

Once the court reaches a decision at the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal, a party may still appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada.

The FEDGOV has proposed the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act (GGPPA), which sets out the legislative framework for what they called the “Backstop” in the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change and later detailed in their Technical Paper. The FEDGOV has issued further statements about how carbon pricing will work specifically in Saskatchewan.

The GGPPA applies to those provinces who did not have in place their own carbon pricing framework that met the federal standards by 2018. The basic carbon pricing plan for Saskatchewan as outlined in the GGPPA consists of two main parts:

- Part I: A price on fossil fuels paid by registered producers and distributors starting in April 20192; and

- Part II: A separate output-based pricing system for facilities related to electricity generation and natural gas transmission pipelines that emit over 50 kt of CO2 equivalent per year. Smaller facilities that emit 10 kt tonnes or more of CO2 equivalent per year can voluntarily opt-in to the system over time.3

The carbon pricing plan ensures that any revenue raised will return to the province of origin to provide relief to vulnerable sectors/individuals and families and as support for other greenhouse gas emission reduction strategies in the province.

View a set of infographics here to better understand carbon pricing and the federal legislation.

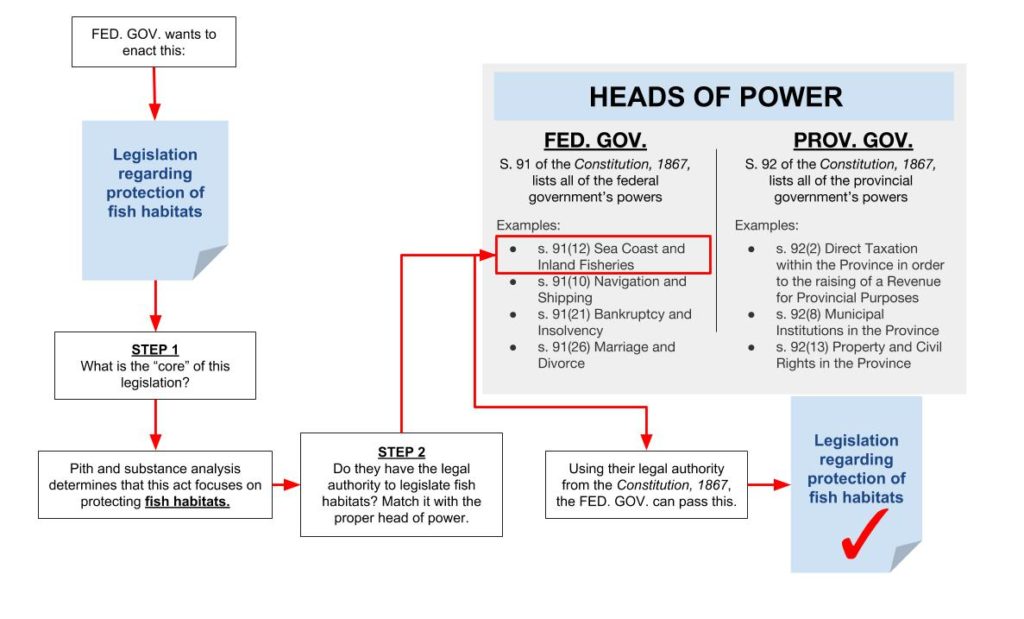

Each level of government has areas of powers designated to them called “heads of power”, which the Constitution Act, 1867 outlines in section 91 and 92.

Sections 91 and 92 define the boundaries within which governments can act (the “division of powers”). Legislation passed by either level of government may be unconstitutional if that law does not fall under any of the respective government’s heads of power. In other words, the government has acted without legal authority. These limitations prevent the provincial government from legislating over matters that the federal government has responsibility over and vice versa. Preserving this balance of powers is a pillar of constitutional law and our systems of government.

Constitutional analysis is a bit like a matching game in which the courts take the piece of legislation at issue and “match it” with one of the powers given to the enacting government by the Constitution Act, 1867. If the courts find an appropriate match, they deem the legislation constitutional.

The “matching” process is not usually this simple, however. The courts must first determine the “core” of the legislation (through the “pith and substance analysis”) and whether it is constitutionally appropriate to categorize it under a certain head of power. This process is further explained below.

STEP 1: Determine the “Core” of the Legislation

Before you can “match” legislation to a head of power, the legislation must be properly “characterized”. In order words, we must determine what subject matter it is legislating or the act’s “core”/”essence”. This is what the courts call the “pith and substance” analysis, which is an important step, as legislation may touch on more than one subject matter.

For example, an act called “The Protecting Fish Habitats Act” may involve much more than protecting fish habitats. If the act involves taxing fisheries as a way to discourage some industry practices, the legislation now involves matters of regulating businesses and taxation – if the courts determine that either of these matters is the act’s “core”, rather than simply the protection of fish, the court may match the act to a head of power other than s. 91(12) Sea Coast and Inland Fisheries.

In examining the “essence” of a piece of legislation, the court will typically look at

- The purpose of the law;

- The legal effect of the law (what impact(s) would the law have if it functions as intended?); and

- The practical effect of the law (what impact(s) would the law actually have?).

STEP 2: “Matching” the Legislation to a Head of Power

The second step involves determining what head of power allows the government to pass the legislation in question – but what exactly do powers like “Sea Coast and Inland Fisheries” or “Criminal Law” mean? What kinds of legislation can be enacted under each of these heads of power? In many cases, the courts have developed “tests” to help them determine whether legislation fits the scope/’requirements” of that head of power. For example, if federally-proposed legislation passes the “test” of one of the federal government’s heads of power, they have the legal authority to enact that legislation.

Constitutional analyses can be especially difficult for matters that did not get drafted into the Constitution and assigned to a particular level of government, like the environment. As a result, both the province or federal government can pass legislation regarding the environment, but they must still do so using one of their existing heads of power.

Read more about constitutional law here.

We have written summaries of the GOVSK’s factum4, the FEDGOV’s factum, and GOVSK’s reply factum, for a more in-depth exploration of their positions:

The main positions are below:

- The GOVSK argues that the GGPPA is unconstitutional for the following reasons:

- Legislation that applies only in provinces who chose not to implement their own carbon pricing violates the principles of federalism (such as provincial autonomy);

- The “core” of the legislation deals with matters that fall under provincial responsibility (ie. local industry) and is therefore outside of the FEDGOV’s areas of responsibility; and

- The GGPPA imposes a tax, and is therefore in violation of s. 53 of the Constitution Act, 18675

- The FEDGOV argues that the GGPPA is constitutional for the following reasons:

- The FEDGOV has legal authority to regulate greenhouse gasses through the GGPPA using the national concern branch of the head of power known as s. 91 Peace, Order, and Good Government (POGG)6. Specifically, the “core” of the GGPPA is to reduce GHG emissions through influencing behaviour, and with that characterization, the GGPPA passes the POGG “test”. Therefore, the FEDGOV can use their POGG power to enact the GGPPA;

- The GGPPA respects the principles of federalism; and

- If the court finds that taxation powers is a more appropriate head of power to group the GGPPA under, that the GGPPA is still validly enacted under this power.

The Government of Saskatchewan is the party bringing the reference question and is challenging the GGPPA as unconstitutional.

The Government of Canada is the intervenor trying to enact the GGPPA.

The following provinces are intervening:

- Ontario (supporting the GOVSK’s position)

- New Brunswick (supporting the GOVSK’s position)

- British Columbia (supporting the FEDGOV’s position)

The following organizations are intervening7 (grouped by application):

- In support of the FEDGOV’s position:

- The Canadian Environmental Law Association (CELA) and Environmental Defence

- Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation

- Climate Justice Saskatoon, National Farmers Union, Saskatchewan Coalition for Sustainable Development, Saskatchewan Council for International Corporation, Saskatchewan Electric Vehicle Club, the Council of Canadians (Regina and Saskatoon chapters), The New Brunswick Anti-Shale Gas Alliance, and Youth of the Earth

- Assembly of First Nations

- The Canadian Public Health Association

- Intergenerational Climate Coalition

- Ecofiscal Commission of Canada

- David Suzuki Foundation

- International Emissions Trading Associations

- In support of the GOVSK’s position:

Footnotes

- https://www.lawnow.org/increasing-importance-reference-decisions-canadian-law.

- Rural and remote residents, farmers, and fishers may be eligible for relief from the carbon pricing

- Part 2 works in conjunction with Saskatchewan's own plan regarding large-industry emitters as outlined in their policy, Prairie Resilience.

- A factum is counsel’s written arguments filed before the court hears the lawyers argue their case. Each level of court and jurisdiction usually has a specific set of rules that lawyers must follow when writing and submitting their factum.

- Section 53 of the Constitution requires any bills related to taxation must be passed democratically, ie., by Parliament.

- The other branch of POGG is known as "national emergency".

- See the order here: https://www.scribd.com/document/395385709/Greenhouse-Gas-Pollution-Pricing-Saskatchewan-Court-of-Appeal-Intervenors